Has SSL become pointless? Researchers suspect state-sponsored CA forgery

The most powerful deterrent against the use of man-in-the-middle attacks against SSL/TLS-encrypted connections may be how much easier it may be to simply attack from the endpoint. Certainly "man-in-the-middle" sounds more sophisticated, and as a pair of well-known academic researchers are preparing to report, the phrase has actually become a "starburst" marketing point for the sale of digital surveillance equipment to government agencies.

But perhaps the most serious defect in the SSL system, allege Indiana University graduate student Christopher Soghoian and Mozilla security contributor Sid Stamm, lies in the ability of government agencies (or individuals acting in the name of government agencies) to acquire false intermediate certificates for SSL encrypted trust connections. Those certificates could enable them to, in turn, sign and authenticate Web site SSL certificates that purport to be legitimate collectors of personal information, such as banks.

In the draft of a research paper released today (PDF available here), Soghoian and Stamm tell the story of a recent security conference where at least one vendor touted its ability to be dropped seamlessly among a cluster of IP hosts, intercept traffic among the computers there, and echo the contents of that traffic using a tunneling protocol. The tool for this surveillance, marketed by an Arizona-based firm called Packet Forensics, purports to leverage man-in-the-middle attack strategies against SSL's underlying cryptographic protocol.

"Using 'man-in-the-middle' to intercept TLS or SSL is essentially an attack against the underlying Diffie-Hellman cryptographic key agreement protocol," reads a Packet Forensics sales brochure obtained by the researchers. "To protect against such attacks, public key infrastructure ('PKI') is often used to authenticate one or more sides of the tunnel by exchanging certain keys in advance, usually out-of-band. This is meant to provide assurance that no one is acting as an intermediary. Secure Web access (HTTP-S) is the best example of this, because when an unexpected key is encountered, a Web browser can warn the subject and give them an opportunity to accept the key or decline the connection. To use our product in this scenario, users have the ability to import a copy of any legitimate key they obtain (potentially by court order) or they can generate 'look-alike' keys designed to give the subject a false sense of confidence in its authenticity."

As the researchers report, in a conversation with the vendor's CEO, he confirmed that government agencies can compel certificate authorities (CAs) such as VeriSign to provide them with phony certificates that appear to be signed by legitimate root certificates.

So if someone is browsing a Web site whose SSL/TLS connection appears to be signed by a legitimate authority, and renegotiation (a big problem for SSL in recent months) enables the certificate securing that connection to be swapped out for a second one that appears to be signed using the same authority (because it was, but on order of a government agency), the browser may not inform the user. Suddenly a surveillance operative is acting as though he'd performed a man-in-the-middle attack like the one described in the sales brochure...but it's not really the same. The operative doesn't break the chain of trust in this scenario; instead, it falsifies the trust.

The researchers have developed a threat model based on their discoveries, superimposing government agencies in the typical role of the malicious user. They call this model the compelled certificate creation attack.

As Soghoian and Stamm write, "When compelling the assistance of a CA, the government agency can either require the CA to issue it a specific certificate for each Web site to be spoofed, or, more likely, the CA can be forced to issue an intermediate CA certificate that can then be re-used an infinite number of times by that government agency, without the knowledge or further assistance of the CA. In one hypothetical example of this attack, the US National Security Agency (NSA) can compel VeriSign to produce a valid certificate for the Commercial Bank of Dubai (whose actual certificate is issued by Etisalat, UAE), that can be used to perform an effective man-in-the-middle attack against users of all modern browsers."

The researchers offered a number of such hypothetical attacks, most of which named governments and real certificate authorities (among them: VeriSign, Etisalat) by name, even though they repeatedly asserted they had no evidence that any of these governments or any of these CAs participated in such activity. "Nevertheless, VeriSign, the largest provider of SSL certificates in the world, whose customers include many foreign banks, companies and governments from countries that do not have friendly relations with the United States, also happens to make significant sums of money by facilitating the disclosure of US consumers' private data to US government law enforcement and intelligence agencies. This fact alone may be sufficient to give some foreign organizations good reason to question their choice of CA," they wrote.

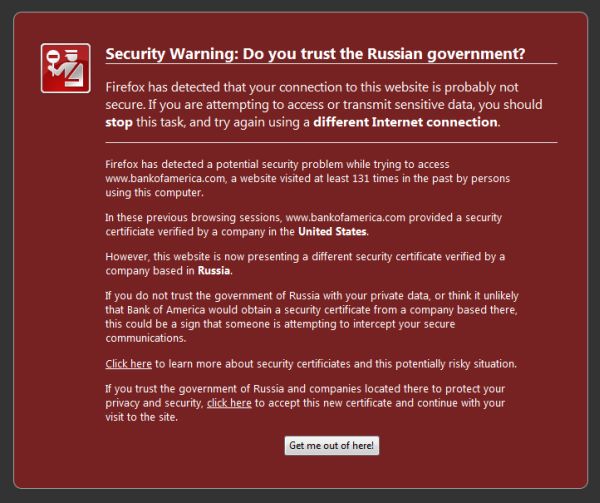

The researchers do have a significant personal interest in this issue: They're working on a Firefox add-on called Certlock, yet to be released, which will augment the warnings Firefox typically presents about unusual certificate behavior. Users will be given the opportunity, for example, to take note when a certificate signing one site has itself been signed by a root certificate authority in another country or district -- for example, a "protected" Hong Kong Web service signed by mainland China.

As Stamm and Sogohian write, "When a user re-visits a SSL protected Web site, Certlock first calculates the hash of the site's certificate and compares it to the stored hash from previous visits. If it hasn't changed, the page is loaded without warning. If the certificate has changed, the CAs that issued the old and new certificates are compared. If the CAs are the same, or from the same country, the page is loaded without any warning. If, on the other hand, the CAs' countries differ, then the user will see a warning."

The question of whether a user should automatically trust all the certificates in his browser's root store, became a sticky one for Mozilla earlier this year. At that time, the organization added the state-run China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) to its store of trusted roots, a decision which upset many Chinese users who have reason to believe China forges its own trust links in order to conduct man-in-the-middle (or from another aspect, "man-at-the-top") surveillance.

"We Chinese users don't trust CNNIC...CNNIC is an infamous organ of the Chinese Communist government to monitor and control the Internet in China," wrote a Mozilla contributor last January, in response to a request for public comment. "For secret reasons they even distributed spyware by making advantage of their administration privilege. They're one of the tools used by the CCP government to censor the Internet users. If CNNIC root certificate is added by default as Builtin Object, they can forge verified Gmail certificates to cheat the Chinese users by using MITM attack against the SSL protocol."

Other contributors agreed there may not be due cause to withdraw CNNIC from Firefox's root store, until specific evidence of claims such as this one emerges. In the meantime, many suggested the browser should arm the user with more information about the nature of the certificates he receives, as well as when and how trusted connections change. The problem with too much information, however -- as Microsoft discovered with Windows Vista -- is that users can eventually come to ignore it.

As another Mozilla participant queried in February, "Legitimate certificates do change over time...even Google has changed certificates a few times recently. Let me ask, how many of you -- yes you, the Internet experts -- have called Google to verify the change of the certificate? Let alone those writers, spiritual leaders, dissidents, farmers deprived of their land, parents whose children were buried in the bribed-to-poorly-built-school and were denied compensation and denied legal assistance, and relatives of Falun Gong practitioners whose organs are taken...You expect them to record and call to verify every certificate change?"